It’s Sunday, November 4, 1979, and my parents look horrified as they watch the evening news. 500 Iranian students loyal to Ayatollah Khomeini seized the US Embassy in Tehran, taking 90 hostages. We had no idea they would be in captivity for 444 days.

I am a sophomore at my college prep high school in Newport Beach, CA. At the time, we have several Iranian students as classmates. We don’t talk to them much. They are quiet, well-dressed, and seem to hang with fellow Iranians. Until that day, we never thought much about them. No different than some of our Indian and Asian classmates.

But the Ayatollah changes all that. In a matter of days, the nation turns anti-Iranian. Now we looked at our classmates with suspicion. One of them, a senior with a thick black mustache with matching eyebrows, wears a suit every day. He carries one of those box-like briefcases your grandpa carried back in the day. We are convinced its full of illicit cash.

We are suspicious, then became angry. In our last varsity football game of the 1979 season, I am a human wrecking machine. A teammate asks me what possessed me. I tell him I visualize a flowing white beard a la Ayatollah coming out from under the facemask of my opponent. I decide to play baseball that spring and a few of us on the JV team come up with a little subgroup we call the AIS. The Anti-Iranian Society. Not that we do anything. We make up little business cards with a skull and crossbones and AIS written above it. Ironically, I print them at the church library where my mom worked for a time. On the ride home from a road game, we start an A! I! S! chant in the back of the van, hitting the floorboard of the van with then ends of baseball bats to keep the rhythm. Coach Johnson rightfully rips us all a new one for that. Today, that would have gotten us kicked out of school, but it was different then.

Americans hated Iranians. My dad’s half-brother Ronald, who is Mexican, is nearly beaten by a mob at a gas station after they thinkt he’s Iranian. Not that it excuses anything, but Americans want revenge. The shame of Vietnam is still fresh as is the recent energy crisis. This hostage standoff pours gas on the fire. I see a shirt at the swap meet that has a picture of the Ayatollah and it says Ayatollah Assahola. I must have one.

Then, on April 24, 1980. Operation Eagle Claw, a complete cluster fuck of a hostage rescue attempt makes the USA look like a drunken fool who just slipped on a banana peel. Tensions are high. We treat our Iranian classmates with contempt. I throw rocks at one of them, Amir, as he walks to the bus stop. I’m not sure why I hate them so much. Maybe it’s because I think they attacked America. I grew up studying WWII history and later building military models and dioramas. I always wondered if I would see war in my lifetime. Maybe we are going to war now. Am I ready?

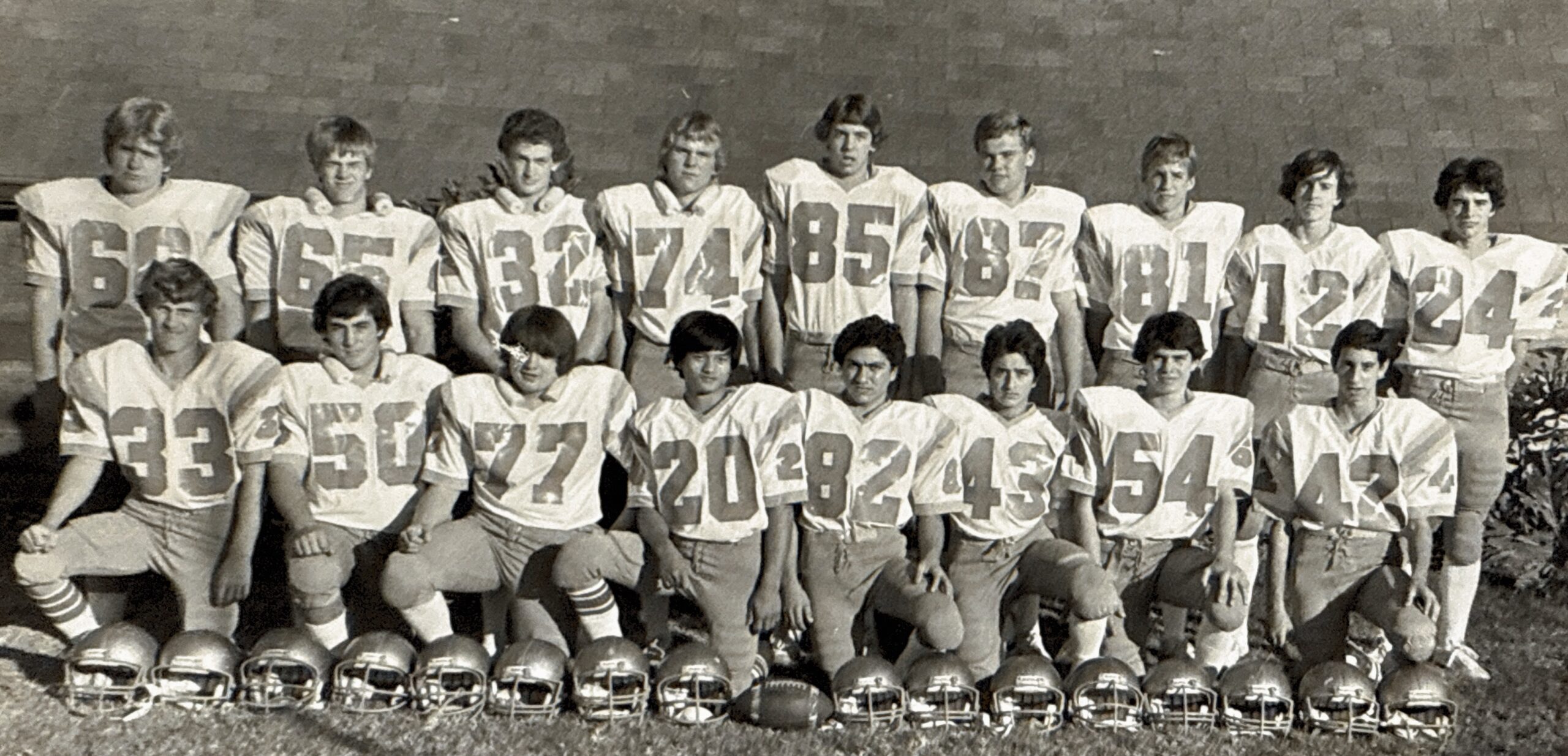

But in early August 1980, as we begin football hell week, we are stunned to see all the male Iranian students coming out to try and make the team. I think they know they are about to get their asses handed to them on a silver platter. They try anyway. We don’t hold back. But the harder we hit them, the more they come back. By the end of summer practice and the beginning of the season, we have mended fences. They all make the team. Some play very well. I think it was the fact we went through hell together makes us realize our new teammates want the same things we do. Peace and freedom. Our classmates and teammates don’t hate America. They don’t hate us. They don’t support that old bearded fuck Ayatollah Khomeini. They hate him as much as we do.

By my senior year, the hostage crisis has been resolved. Now we’re all pondering our future. I’m one of the few in my class not going to college. After graduation in 1982, we go our separate ways.

In 2000, there is a new website called Classmates.com. Someone from our now shuttered high school starts a group and many of us reconnect. Since our school was a small one, the group comprises many graduate years. Eventually, a few alumni organize a reunion in Southern California. I decide to go since it will give me a chance to visit my grandmother who is nearing 90.

In June of 2001, I fly back to California to attend the reunion. It includes years up until the late 1980s when the school closed. I haven’t seen most of these folks in 20+ years. Some have aged well. Some have just aged.

It’s a three-day event. On the first night, I leave LAX and head down to the Huntington Beach Harbor. There is a dinner and a bar on a boat. The very boat we used in high school for Oceanography class. On the evening of Day #2, we have a party in Hollywood, and then our Iranian classmates invite us to go out to Westwood, where they live, near the UCLA campus for drinks and food.

“What is the second most common language spoken in Westwood?” Shariar asks.

“English! Farsi is first.” We all laugh.

They order for us. Some strange Persian food. I am hoping all the AIS shit is long forgotten. I don’t know if this food was payback for that! It’s really good. I just don’t quite know what it is.

After a few drinks, some truth comes out. Kambiz and Shariar tell us they went through high school alone. In their own apartment. Their parents sent them out of Iran as young teenagers when things began going South. We had no idea they were all alone. Nobody shopped or cooked or cared for them. I can’t tell you how ashamed I am that I treated them like terrorists simply because they shared the same nationality of some bad guys several thousand miles overseas. And I had no idea they were alone, likely homesick and frightened.

It’s wonderful to reconnect. We stay out until well after 1AM. The next day we have a big picnic where our alumni bring their families. It’s a great time and since this is before Facebook, the experience of seeing people for the first time in decades is amazing.

We all vow to stay close in touch. Kambiz calls me as I boarded my flight back to IAD. Earlier we hugged and vowed to stay in touch. Sadly, we did not keep that promise.

As expected, none of us managed to stay connected. I heard from my ex a few years later that when one of her step kids fell out of their van and had to go the ER, that Dr. Shariar Alikhani took care of her. That made me feel good.

My one big regret from that reunion was that I didn’t ask Kambiz and Shariar for forgiveness. I think this has bothered me more just in the last few years. For some strange reason.

The easiest thing to do, I’ve discovered, is to rush to judgement based on a few pieces of information combined with a whole lot of bias and stereotyping. And here is the danger:

“Everyone is fighting a battle you know nothing about.” Ian Maclaren.

That means all of us. So let’s cut each other some slack. And do our best to show and express some empathy for our fellow member of the species.